By Lynn Venhaus

A bold, ambitious “A Streetcar Named Desire” is the centerpiece in this year’s 10th annual Tennessee Williams Festival St. Louis.

A contemporary interpretation of the playwright’s most iconic work nearly 80 years after his masterpiece stunned Broadway audiences, director Michael James Reed asks us to look at the Pulitzer Prize and Tony-winning drama with fresh eyes. He prefers the term ‘reconstruction’ instead of ‘deconstruction,’ and that is what he delivers.

Already a relic from the past, fading and fragile Southern belle Blanche DuBois arrives at her sister Stella’s doorstep, to stay at her run-down two-room flat. Stella’s brutish working-class husband Stanley Kowalski isn’t aware of her visit and, immediately agitated, locks horns with his attention-seeking sister-in-law.

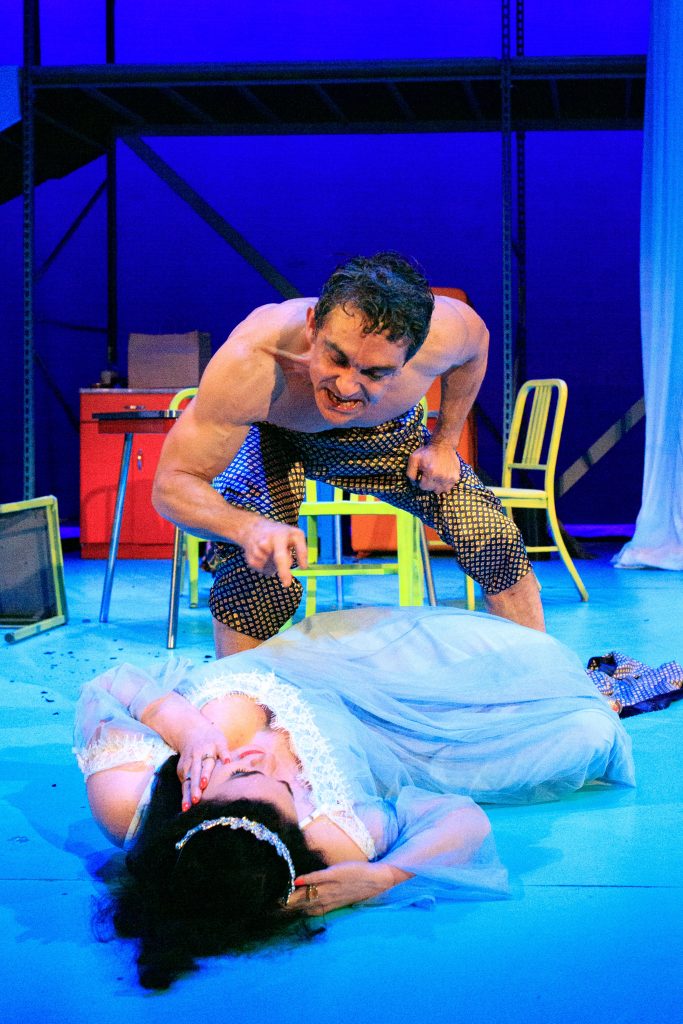

Over the course of the stifling summer, tempers flare, and Stanley becomes increasingly volatile, his bullying obsessive, while Blanche unravels – her displacement, discomfort and disorders adding to her breakdown. Stanley’s verbal and physical abuse becomes too much, leading to sexual abuse.

This doomed power play leaves wreckage from a predator and prey situation, for Blanche appears like a frightened caged animal, her feminine wiles no longer effective.

Her final line, as she clings to a gentle doctor (David Wassilak) escorting her away: “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers” is shattering.

The cast portrays these indelible roles through a lens that is both rooted in Tennessee Williams’ dysfunctional framework and then Reed’s challenge to bring something different to their characterizations.

Some of the choices go outside the lines of our perceptions — with Todd D’Amour’s tightly wound abusive Stanley displaying pathological cruelty, Beth Bartley’s grittier desperate Blanche masking her many indignities, and Isa Venere’s younger Stella enabling and helpless. Think of it as an American horror story in retrospect.

As the local festival has amplified the past 10 years, Williams’ works are about loss in some way – of beauty, love, youth, identity and/or way of life, and this manifests through a range of characters developed during a career spanning 50 years, from the 1930s to his death in 1983 at age 71. After “The Glass Menagerie” made him a rising star in 1944, he opened 14 plays on Broadway from 1947 to 1980.

This is the first time that I really felt Williams’ own torment, of how humiliating it was for him to work with bullies like Stanley at the International Shoe Company during his formative years here, at a time when he was not free to express his sexuality and there was a very specific masculine ‘standard’ in society, not to mention another variation on his beloved sister Rose, mentally challenged at a time it was not understood. His own feelings poured out in these characters.

Looking back today, one sees societal changes colliding in Williams’ most famous work –the new South vs. the past, and women’s evolution regarding gender roles.

Post-war America, during this long, hot summer on Elysian Fields Street, adjacent to the French Quarter of New Orleans, we feel the heat. Sometimes, the atmosphere feels suffocating without any relief, while other times it feels like the tension is so thick and volatile, it could combust.

In that setting, the raw intensity seeps through, revealing harsh truths and emphasizes Williams’ timeless themes of illusion, trauma, power, control, and desire, and when reality hits head-on, how it changes expectations.

After the play debuted to a thunderous 7-minute standing ovation on Dec. 3, 1947, it was adapted into an acclaimed Academy Award-winning film in 1951, with three of the four principals reprising their roles– Marlon Brando, Kim Hunter and Karl Malden, but Vivien Leigh as Blanche instead of Jessica Tandy.

Let’s face it, comparisons are inevitable, and “Streetcar” continues to be performed around the globe, never out of view. Andre Previn’s 1998 opera is part of Opera Theatre of St. Louis’ line-up next summer and a 2022 London play revival transferred to off-Broadway earlier this year for a limited run starring acclaimed Irish actor Paul Mescal, who won an Olivier Award as Stanley, and Spanish-British actress Patsy Ferran as Blanche.

The roles are demanding because they can easily go over-the-top into caricatures. After all, their indelible work has been exaggerated into comic archetypes in pop culture for decades.

Bartley’s panicked Blanche reunites with her sister, and Venere’s Stella, goes into caretaker mode, even when she learns that their family estate, Belle Rive in Laurel, Mississippi, has been lost to creditors.

A traumatized Blanche recalls taking care of their dying relatives without help. She says she has taken a leave of absence from teaching high school literature because her nerves are so frayed. Bartley and Venere share a comfortable chemistry.

Enter suspicious, coarse and crude Stanley. D’Amour isn’t imposing, nor is he articulate. With mumbled lines, he’s hard to understand and harder to relate to, and that’s unfortunate because it throws the balance off.

Stella, caught in the middle, must try to keep the peace between the warring factions, but she is ineffective. She and Stanley share a tempestuous sexual attraction, and his aggressive domestic violence is despicable (never acceptable, no matter what era, but being a batterer fits his offensive personality).

While Stanley seethes, Blanche makes herself at home, languishing in the bathtub, lounging in their shabby quarters, secretly drinking, and putting on her Southern Belle airs.

With her fanciful ways, she attracts an admirer — Stanley’s war buddy and poker-playing friend, Harold “Mitch” Mitchell (Eric Dean White), a bachelor who lives with his ailing mother. A raging Stanley will destroy that tender union after uncovering Blanche’s scandalous secrets back home.

Trembling like an older, needier Judy Garland, whom she resembles, and acting delusional like the moody narcissistic Norma Desmond in “Sunset Boulevard,” Bartley is heart-breaking living out a fantasy life while she is clearly in decline. Now that we know more about mental health, it’s obvious Blanche has Histrionic Personality Disorder.

It’s a devastating portrait, and she also reveals a skilled manipulator, who has managed to survive using the theatrical tools in her toolbox.

As Mitch, White shows his sweet side, and two lonely people find comfort in each other. She’s flirtatious while she tells tall tales, and he’s smitten. When he confronts Blanche with what he’s discovered about her many liaisons and seductions in her hometown, though, his anger is visible – he’s done with being a nice guy.

The other supporting characters are lived-in examples of the area – top-shelf veterans Emily Baker and Isaiah DiLorenzo are their loud neighbors (and landlords) Eunice and Steve, who live upstairs. DiLorenzo and Wassilak are the two cast members that were in the festival’s award-winning 2018 “Streetcar” production.

Jeremiah King is a young collector, Cedric Leiba Jr. is another poker player, and Gwynneth Rausch is a nurse. Offstage, Jocelyn Padilla voices a flower collector. She also served as the intimacy coordinator. Jack Kalan was the fight choreographer.

Both Matthew McCarthy’s moody lighting design and Phillip Evans’ sound design are strong in this production, with dramatic illuminations and a discordant cacophony and jazzy-blues music adding to the atmosphere.

Two elements puzzled me. For a story that emphasizes claustrophobia in such small quarters, the set design did not appear so. Patrick Huber favored a nod to mid-century modern décor, with a neon palette more suited to another era or pre-school, that was stretched out on the Grandel stage.

Shevare Perry’s costume design for most of the cast worked fine, but Blanche’s daytime outfits appeared misfitting and Stella’s pants in the opening scene were jarring. Blanche’s flouncy nightgowns and bright red satin robe were just right.

Perhaps those choices were all in keeping with tossing out pre-conceived notions for this production.

“A Streetcar Named Desire” maintains its power in Williams’ vivid poetic realism and lyrical dialogue that continues to captivate. While I prefer more emotionally charged character renderings, which was what Blanche aimed for, instead of a detached one like Stanley and Stella, these were choices made for a different take. In real life, D’Amour and Bartley are married.

Williams’ view of outsiders, of deeply flawed humans, continues to resonate some 80 years later, and that’s worth celebrating.

The Tennessee Williams Festival presents “A Streetcar Named Desire” Aug. 7 – 17 at the Grandel Theatre in Grand Center. For more information, visit www.twstl.org

Lynn (Zipfel) Venhaus has had a continuous byline in St. Louis metro region publications since 1978. She writes features and news for Belleville News-Democrat and contributes to St. Louis magazine and other publications.

She is a Rotten Tomatoes-approved film critic, currently reviews films for Webster-Kirkwood Times and KTRS Radio, covers entertainment for PopLifeSTL.com and co-hosts podcast PopLifeSTL.com…Presents.

She is a member of Critics Choice Association, where she serves on the women’s and marketing committees; Alliance of Women Film Journalists; and on the board of the St. Louis Film Critics Association. She is a founding and board member of the St. Louis Theater Circle.

She is retired from teaching journalism/media as an adjunct college instructor.