By CB Adams

It is a rare pleasure to encounter “Salome,” Richard Strauss’s 1905 masterpiece (after Oscar Wilde’s scandalous play), on a St. Louis stage. Union Avenue Opera’s production reminds us that even in a modest house, this one-act psychodrama retains its power to disturb.

The evening offered superlative singing across the board, a moody if sometimes murky staging and Strauss’s extraordinary score rendered with clarity and bite by a chamber-sized orchestra that, under Scott Schoonover, sounded far larger than its 23 players.

The vocal achievement was formidable. St. Louis’s own Kelly Slawson brought fearlessness and stamina to the punishing title role, her dramatic soprano slicing cleanly through Strauss’s post-Wagnerian textures. The part notoriously demands everything from flights of coloratura to plunges into the contralto register along with sheer brute endurance.

Slawson met those challenges with assurance, shaping a Salome who was as predatory as she was magnetic. She infused the role with a heavy-metal intensity — thrilling, unsettling and never bland.

Opposite her, baritone Daniel Scofield supplied a commanding Jochanaan, his resonant timbre and prophetic fire holding the line against Salome’s obsessive advances.

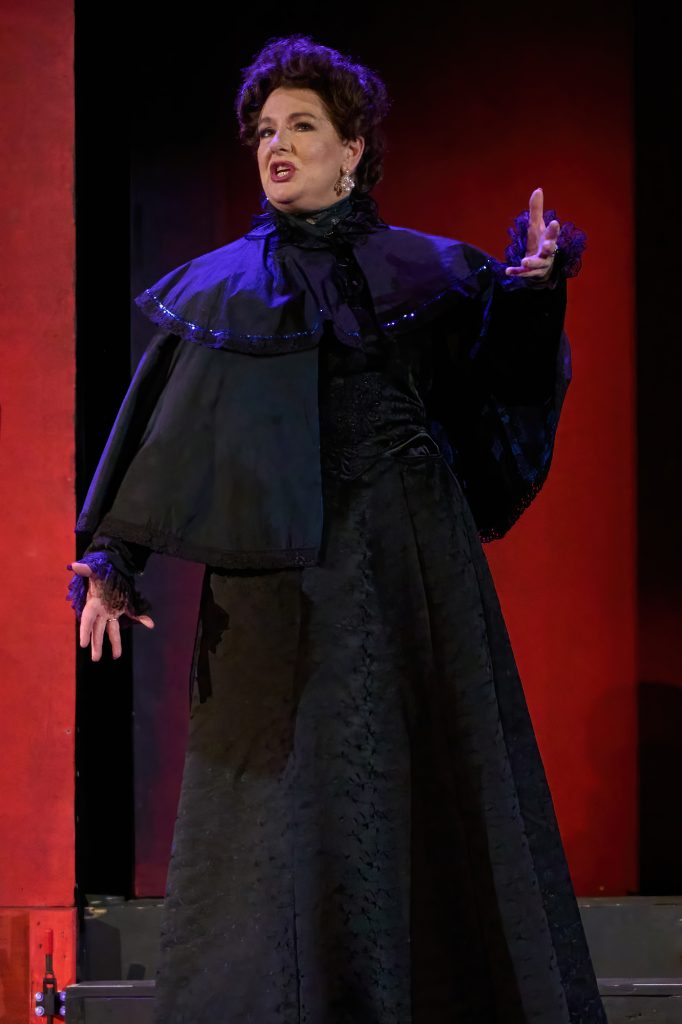

Will Upham’s Herod was appropriately febrile, a portrait of jittery decadence, while Joanna Ehlers’s Herodias offered caustic bite and a Wildean cynicism delivered with relish.

Brian Skoog (Narraboth) brought pathos to his brief trajectory, Emily Geller (the Page) added androgynous ambiguity and the quintet of Jews (Zachary Devin, Thomas M. Taylor IV, David Morgans, James Stevens, Fitzgerald St Louis) bickered with crisp ensemble precision. It was a cast without weak voices.

For all its musical strengths, the staging stumbled at two moments of dramatic consequence. The first misstep came early in the opera with Narraboth’s suicide. Poorly blocked, the scene left the audience’s eye on Salome rather than the lovesick captain.

His awkward, almost perfunctory thrust of the sword could have been missed entirely, thereby diluting Herod’s subsequent questions about the bloodied corpse. What should resonate as the opera’s first shocking rupture barely registered.

Will Upham and Joanna Ehlers. Photo by Dan Donovan.

The Dance of the Seven Veils, the opera’s centerpiece, likewise faltered. Slawson committed herself wholly, but the choreography lurched from abrupt pivots to ground- wriggling, from a parody of Norma Desmond to burlesque flourishes, all without discernible logic. A needless ascent and descent of the steps only deepened the sense of randomness.

At one point she barked toward the chorus; at another, the sequence spun into manic incoherence. The result brought to mind Brad Pitt’s turn in “12 Monkeys” — all nervous tics, sudden lunges and wide-eyed mania, as though every acting exercise had been flung on stage at once.

In a film, that kind of method-to-madness can be riveting; in this opera, it scattered the focus of a moment that should be singularly hypnotic. As a seduction meant to clinch the opera’s fatal bargain, the dance distracted rather than compelled — a pity, given the strength of the surrounding production.

Schoonover drew exceptional results from the orchestra. Strauss scored “Salome” for more than a hundred musicians, but Union Avenue performed it using Francis Griffin’s reduced orchestration for 23 players. In Schoonover’s hands, the ensemble produced a luminous, incisive sound that never swamped the singers while still carrying the music’s unsettling erotic charge.

Union Avenue’s “Salome” deserves praise as a rare and rewarding opportunity (despite its missteps) to encounter Strauss’s modernist milestone. Vocally and musically, it was a triumph; dramatically, it remained absorbing despite missteps. For audiences willing to face opera at its most decadent and disturbing, this production more than justified the journey.

Union Avenue Opera’s production of “Salome” was performed Aug. 15, 16, 22 and 23 at the Union Avenue Christian Church

Emily Geller, Brian Skoog. Photo by Dan Donovan

CB Adams is an award-winning fiction writer and photographer based in the Greater St. Louis area. A former music/arts editor and feature writer for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, his non-fiction has been published in local, regional and national publications. His literary short stories have been published in more than a dozen literary journals and his fine art photography has been exhibited in more than 40 galley shows nationwide. Adams is the recipient of the Missouri Arts Council’s highest writing awards: the Writers’ Biennial and Missouri Writing!. The Riverfront Times named him, “St. Louis’ Most Under-Appreciated Writer” in 1996.