By CB Adams

Opera Theatre of Saint Louis has always balanced reverence for tradition with a bold embrace of innovation, and its 50th anniversary season is no exception. The world premiere of “This House,” a new commission, looks squarely at the present and future of American opera (through and examination of the past), while the season’s revival of Donizetti’s “Don Pasquale” casts a backward glance—albeit through a sharply contemporary lens.

In remounting the company’s inaugural production from 1976, director Christopher Alden returns not with nostalgia, but with a bracingly modern aesthetic that reimagines the comic core of “Don Pasquale” as a meditation on aging, delusion and desire.

Alden, known for his psychologically incisive and visually stylized productions, sets the action in a Rococo-inspired espresso bar (by way of Botero and Fellini) populated by grotesque old men—figures who mirror the titular character’s absurd longing for youth. The setting is witty and revealing, a hallmark of Alden’s work, and it allows the production to comment on the opera’s themes without sacrificing its buoyant charm.

Sheri Greenawald, who played Norina in the original 1976 staging, returns in a newly created role as the espresso bar proprietor and faux notary. Though the role is modest in scale, Greenawald’s presence is quietly commanding, and her final duet with Susanne Burgess adds a poignant, intergenerational resonance to the production.

The creative team is uniformly strong. Marsha Ginsberg’s set and costume designs are richly evocative, from the frescoed walls and oversized granite-patterned floor to the exaggerated silhouettes that underscore the opera’s farcical elements.

Krystal Balleza and Will Vicari’s wigs and makeup heighten the grotesquerie, while Eric Southern’s lighting and the inventive use of video and shadow in Act Three add layers of visual storytelling. Seán Curran’s choreography, particularly in the Act Two finale, is a kinetic delight, echoing the protagonist’s unraveling psyche with physical wit.

One of the most striking aspects of this production is its use of English—a choice that proves both practical and profound. While operas often lose some of their musicality or nuance in translation, this Don Pasquale gains immediacy and clarity, allowing the humor and emotional stakes to land with unforced precision with an English translation by Phyllis Mead. The vernacular enhances accessibility as well as also deepens the audience’s connection to the characters’ foibles and desires.

This aligns with a long-standing debate in American opera circles, dating back (at least) to 1908 when critic Henry Krehbiel observed that opera in America would remain “experimental” until “the vernacular becomes the language of the performance and native talent provides both works and interpreters.”

More than a century later, Opera Theatre of Saint Louis proves the prescience of Krehbiel’s vision. By embracing English, the company underscores its commitment to making opera a living, breathing art form—rooted in tradition, yet unmistakably of the moment.

This linguistic approach also distinguishes OTSL within the broader St. Louis opera landscape. While OTSL performs exclusively in English to foster immediacy and inclusivity, Union Avenue Opera often presents works in their original languages, preserving the musical and cultural authenticity of the repertoire. Winter Opera St. Louis similarly favors original-language performances, particularly in its focus on classic Italian and French works.

Together, these companies offer a rich spectrum of operatic expression—balancing accessibility with tradition—and contribute to a vibrant, multilingual arts scene that reflects the diversity and sophistication of St. Louis’s theater and entertainment culture.

Musically, the production is anchored by Kensho Watanabe’s elegant conducting of the St. Louis Symphony, which brings Donizetti’s score to life with warmth and precision. The orchestra does more than underscore the action; it articulates its momentum, its pauses, its turns.

Far from a passive presence in the pit, it engages in a dynamic exchange with the stage—less an accompaniment than a co-author of the drama. Watanabe’s sensitivity to the singers and the comic pacing of the bel canto style is evident in the subtle dynamics and impeccable timing throughout.

The chorus, under Andrew Whitfield, is a comic force in its own right, first as leering old men and later as a chorus of women under Norina’s rule.

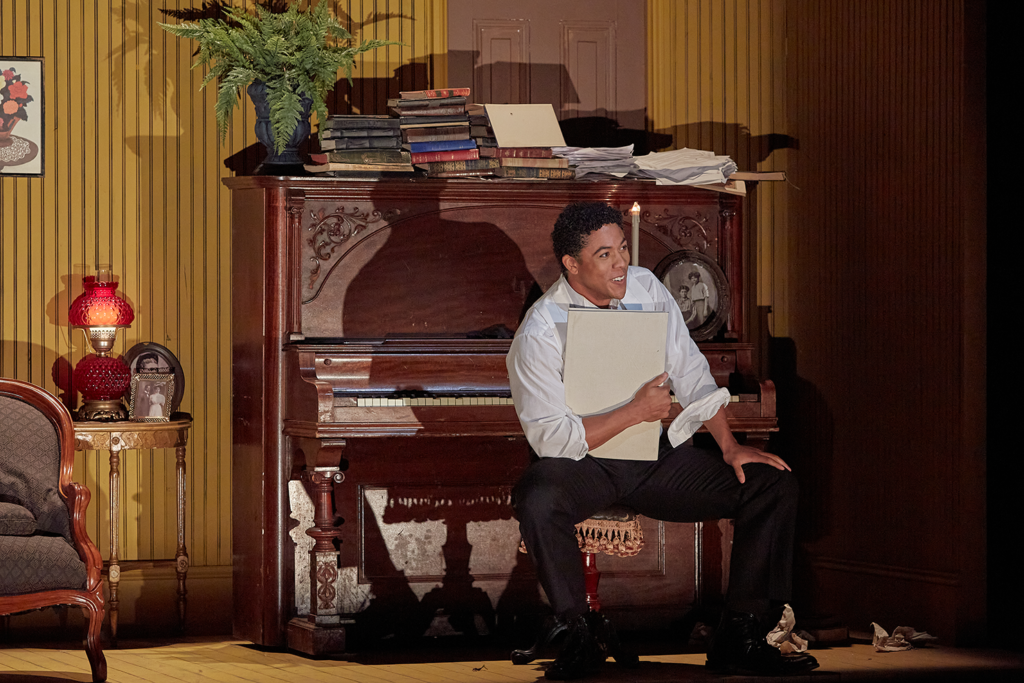

Among the principals, Patrick Carfizzi’s Don Pasquale is a masterclass in comic timing and pathos. He brings clarity and vocal lucidity to the role, embodying the pompous bachelor with a mix of bluster and vulnerability. Kyle Miller’s Malatesta is a charismatic schemer, his bold baritone matched by an energetic, almost acrobatic stage presence.

The ongoing sight gags with his pork pie hat were a nice touch of visual whimsy and an indication of the level of attention to detail that reveals the production’s quality (that is, they sweated the details).

Charles Sy’s Ernesto offers a sweet, lyrical tenor that soars in his serenade to Norina, a moment of romantic magic that culminates in a duet of sublime beauty. As Norina, Susanne Burgess dazzles with a performance that is both vocally virtuosic and emotionally grounded.

Her coloratura passages are delivered with effortless charm, and her comedic instincts are as sharp as her high notes are stratospheric. If forced to choose from the cast, Burgess’ performance was a knock-out, stand-out.

Adding to the comic texture is baritone Patrick Wilhelm in a delightful turn as the waiter-servant-factotum. His silent antics—managing Norina’s extravagant gown, delivering messages with canine devotion, and bouncing through scenes with Chaplinesque flair—contribute to the production’s surrealist tone.

That surrealism is further amplified by Alden’s visual wit: Don Pasquale perched Edith-Ann-like (ala the vintage “Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In” television show) in an oversized chair; a veiled Sofronia wheeled in on a dessert cart like a birthday surprise; and a lavish shopping spree that name-drops every luxury brand from Armani to Ferrari.

Norina’s ritzy entourage spans a spectrum of chic identities, and her redecorating spree replaces Pasquale’s furnishings with pastel sectionals, which he and Malatesta later use to build a childlike fort.

Ernesto’s serenade is staged with a projected silent film of the lovers strolling through a wooded glen, and silhouette play cleverly underscores the shifting power dynamics—Pasquale literally diminished in Norina’s towering presence.

At one point, the cast unfurls a banner reading “VIVA LA RESISTENZA,” a gesture that flirts with political commentary but is so deftly woven into the scene that it feels both subversive and theatrically organic—especially as it culminates in the mummy-like wrapping of Sheri Greenawald’s character, blurring the line between satire and stagecraft.

This Don Pasquale is a vivid example of theatrical reinvention. It bridges past and present, celebrating five decades of OTSL’s forward-looking vision. At the risk of sounding highfalutin, this production exemplifies Regietheater—director’s theater—a mode of staging that has become ubiquitous across the global opera landscape.

Yet ubiquity does not guarantee success. What distinguishes this production is how deftly Christopher Alden wields the tools of Regietheater to craft a theatrical experience that is as intellectually stimulating as it is viscerally entertaining. In his hands, Donizetti’s comedy becomes something richer, stranger and altogether more delightful. It’s a production not to be missed.

Opera Theatre of St. Louis’ production of “Don Pasquale” continues in repertory at the Loretto-Hilton Center of Performing Arts at Webster University through June 29. For more information, visit https://opera-stl.org.

CB Adams is an award-winning fiction writer and photographer based in the Greater St. Louis area. A former music/arts editor and feature writer for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, his non-fiction has been published in local, regional and national publications. His literary short stories have been published in more than a dozen literary journals and his fine art photography has been exhibited in more than 40 galley shows nationwide. Adams is the recipient of the Missouri Arts Council’s highest writing awards: the Writers’ Biennial and Missouri Writing!. The Riverfront Times named him, “St. Louis’ Most Under-Appreciated Writer” in 1996.