By Alex McPherson

Utterly mesmerizing, acclaimed director Albert Serra’s “Afternoons of Solitude” showcases beauty and bravery walking hand-in-hand with barbarism — forging a complicated portrait of bullfighting as a tradition of spectacle and destructive consequence.

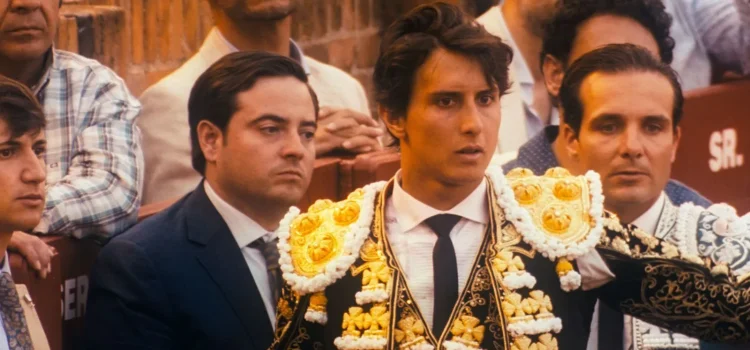

Serra’s film, his first documentary, eschews narration, onscreen text, and talking-heads interviews to immerse us into the world of celebrity matador Andrés Roca Rey over the course of three years across Spain. Serra’s focus is selective; we don’t actually learn much about Roca outside of bullfighting, observing him solely from the context of his day-to-day, high-stakes occupation.

Trimmed down from nearly 600 hours of footage, Serra mainly presents Roca in three contained environments: the packed stadiums where he faces off against his bovine adversaries; the high-class hotels he stays in; and the van (packed with hype men who wax pseudo-poetic about the size of his testicles while giving his exploits soulful importance) that shuttles him between the two. We also sometimes concentrate on the bulls raised for slaughter in these arenas of death. The opening scene, in fact, forces us to stare directly into their eyes in a way that conveys both their raw power and ultimate powerlessness.

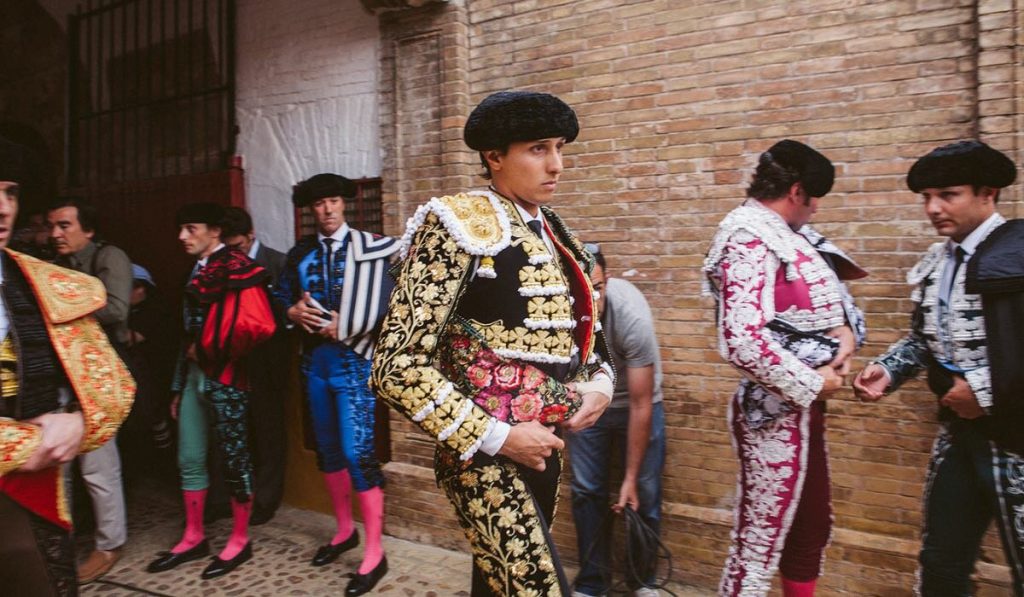

Serra underlines the repetition of Roca’s day-to-day life — cleaning up his injuries, meticulously donning his flamboyant clothing (occasionally being hoisted into them), saying his prayers, and risking his life for roaring crowds against a dazed and hypnotized creature stripped of agency. We also witness his later reflections on the experience as his team smooths over his sporadic self-doubt over his success and masculinity in preparation for the next go around.

It’s hypnotic and deeply disturbing — presented at a remove that separates the “entertainment” from Roca’s performances in the arena and from behind closed doors, capturing the allure and repulsion of a controversial practice.

Indeed, the ironically titled “Afternoons of Solitude” is a participatory viewing experience, urging us to come to our own conclusions, yet always making us aware of the inherent absurdity and toll of the sport. Bringing to mind a more conventionally cinematic Frederick Wiseman, Serra’s approach draws special attention to form, specifically what is centered in the frame and what isn’t, building a gradually comprehensive picture of the dangers and perverse thrill of bullfighting.

Time and time again, we observe Roca’s stoicism and pangs of nervousness, his bravery risking his life, and the bulls’ heartbreaking final moments in which light drains from their eyes and their carcasses are unceremoniously dragged off into the shadows, soundtracked to a roaring, unseen crowd.

Serra presents this cycle of events as routine, but the violence and the subjects’ detachment from said violence never loses its shock value, particularly in the attention Serra pays to the bulls themselves, and in the almost cartoonish conversations Roca has with his entourage afterwards. The deadly stakes at play (brought up in reference to Roca’s retired colleagues and fellow competitors) only momentarily break through in their discussions as Roca prepares to face the next challenge, and their worries are discussed in private.

Serra effectively puts us in the arena with Roca, but from an audience perspective and heavily zoomed-in. We’re simultaneously in the thick of it while still being at a remove. This works to showcase the elaborate performance that Roca puts on — almost transforming into a different being himself — and giving Serra the ability to navigate the space and subtly guide our attention through his camera, whether it be on Roca’s athleticism and endurance, the bulls’ anger and suffering, or the weirdly banal repetition of Roca’s movements, punctuated by startling jolts when his “control” slips away and the captor becomes the attacked.

Stripped of the “fun” that the crowds are drawn to, what we’re left with is monstrousness disguised as entertainment: a thousand-year-plus practice that’s likely here to stay. Roca, too, drawn to stardom and attention but still vulnerable to fear (his hypemen have to train him mentally like an animal in some instances), is clearly devoted to the craft, and has no intention of stepping down. Serra posits that bullfighting is the essence of who Roca is, having given himself over fully, and potentially fatally, to his art.

Marc Verdaguer’s score notably weaves together dread and strange lightness, eventually resolving in a sense of melancholic acceptance as Roca bows to the audience and walks “off-stage” into the darkness.

It’s all deeply bizarre and unsettling, but above all else ridiculous: acceptance of the abominable in the service of bloody tradition. But that’s just my takeaway — “Afternoons of Solitude” leaves the door open for viewers to make their own meaning. And that’s a large part of its absorbing, horrifying brilliance.

“Afternoons of Solitude” is a 2024 documentary directed by Albert Serra about bullfighting. Its runtime is 2 hours, 5 minutes and it screens at the Webster Film Series July 25-27. In Spanish. Alex’s Grade: A+

Alex McPherson is an unabashed pop culture nerd and a member of the St. Louis Film Critics Association.