By Alex McPherson

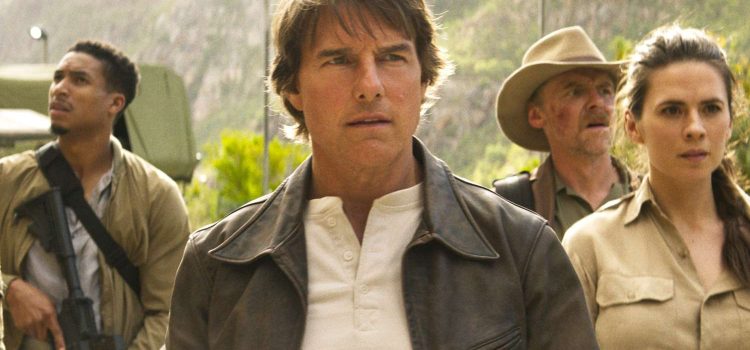

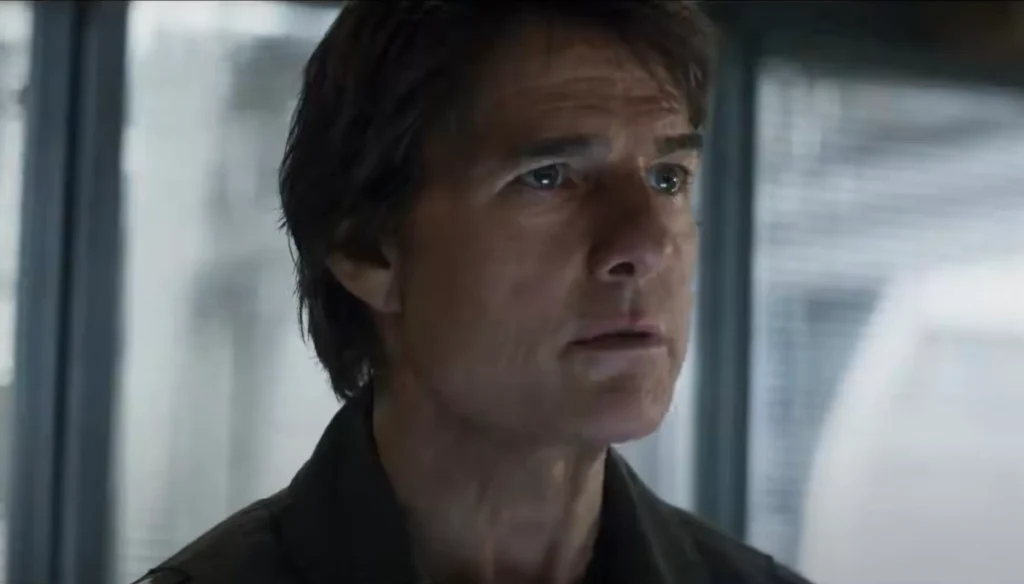

David Corenswet makes an excellent lead in James Gunn’s colorfully zany and overstuffed “Superman,” a film that marks an amusing, if largely unremarkable, revival for the titular world-saver and the DC Cinematic Universe.

Gunn — who previously directed the “Guardians of the Galaxy” films and 2021’s “The Suicide Squad” — doesn’t opt for another origin story here. Rather, “Superman” starts three years after Superman’s aka Clark Kent’s aka Kal-El’s (Corenswet) public debut as the newest “metahuman” on the scene.

Gunn assumes that we’re already familiar with the basics of the backstory, so Superman’s transport to Earth from Krypton and his subsequent upbringing in rural Smallville, Kansas, is conveyed via text, which saves time while sacrificing some emotional heft down the road.

We’re instead launched into the action as Supes plummets down into the frozen tundra in Antarctica. He just lost a battle against “the Hammer of Boravia,” who vows retribution after Superman stopped Boravia’s attempted invasion of its neighboring country, Jarhanpur.

It turns out the Hammer of Boravia is being controlled by Superman’s arch nemesis, the bald-headed baddie Lex Luthor (Nicholas Hoult). Lex has developed his own pair of metahumans and envies Superman’s worldwide popularity. He enlists his legion of followers and sycophants to control the media narrative and paint Superman as an outsider to be banished.

Lex also works with members of the US government (because of course he does), who are growing increasingly wary of Superman’s power and actions, especially since Boravia is a geopolitical ally.

Rambunctious CGI Superdog Krypto (who, thankfully, gets tons of screen time) rescues Superman from an icy fate, roughly dragging him to the nearby Fortress of Solitude, and, with the help of some self-deprecating robots, heals the Man of Steel with solar radiation. Superman is back in action and eager to take down Hammer.

But he has to show up the next day as Clark Kent to work at the Daily Planet, where he’s often publishing one-on-one interviews with himself as Superman. He’s also been dating fellow reporter Lois Lane (Rachel Brosnahan) for three months — she knows his secrets — and navigating some murky waters in their relationship.

Superman’s values of goodness, kindness, and “the right thing to do” butt heads with far-more-complicated reality, particularly regarding his involvement in the war between Boravia and Jorhanpur.

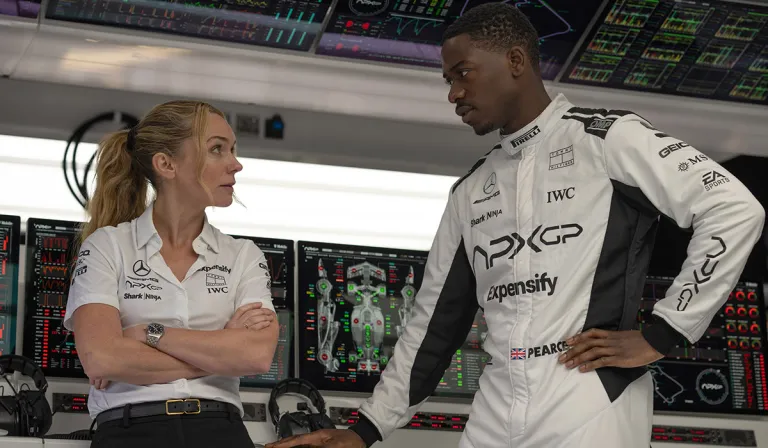

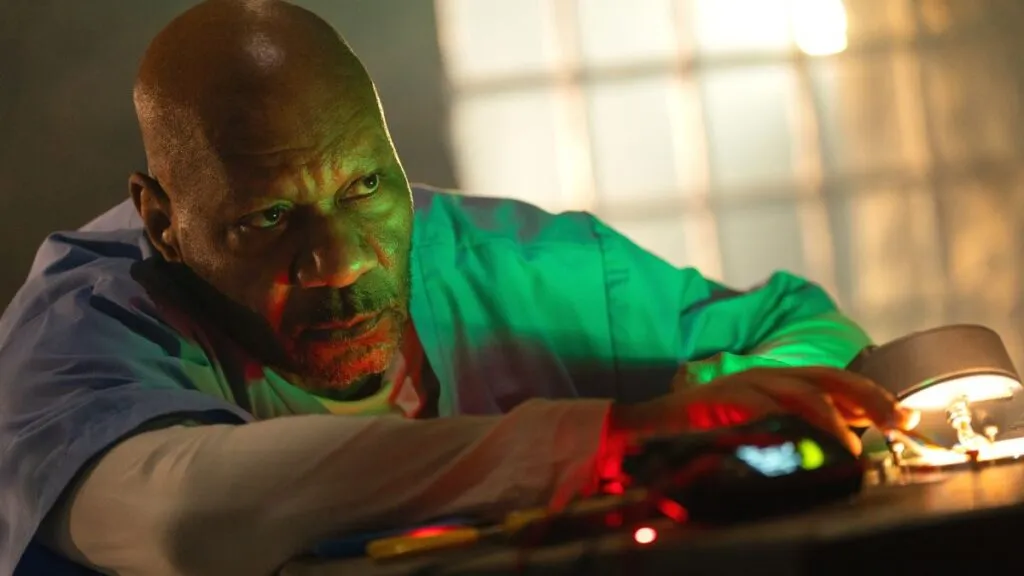

Lex eventually unearths something that rocks the public’s confidence in Superman, and Superman’s confidence in himself. Superman must confront and stand up for what he believes in while getting help along the way from the “corporate-sponsored” Justice Gang — the egotistical Guy Gardner aka Green Lantern (Nathan Fillion), Hawkgirl (Isabela Merced), and Mister Terrific (a scene-stealing Edi Gathegi) — and the intrepid reporters at the Daily Planet. The fate of the world is once again on the line, plus the future of comic book movies in general.

Fortunately, “Superman” delivers where it counts, for the most part. Gunn clearly has passion for the source material and injects his signature blend of wackiness and peculiarity throughout, giving his ensemble space to shine and charm as entertaining versions of characters many of us have grown up with.

What’s also here, unfortunately, is the bloat common to modern superhero cinema. There’s a tension between the film’s surprisingly pointed social commentary and its ultimate reversion to messy spectacle, making this “Superman” more a light trifle than a substantial, memorable meal.

Corenswet is an appealing Caped Kryptonian, corny and dedicated, vulnerable despite his superhuman strength. We don’t get a whole lot of Clark Kent here — his scenes are mostly shared with Lois, portrayed with verve by Brosnahan, in a role that perhaps doesn’t give her enough room to be more than a romantic plot device by the third act — but Corenswet shoulders the weight of Christopher Reeve’s legacy effectively.

Corenswet captures the character’s sincerity, naivete, and, increasingly, self-doubt over the sort of person he is meant to be. He is most successful in the film’s more character-focused moments, like a tense argument with Lois about ethics early in the film, but watching him soar through the air and punch bad guys so hard their teeth fall out remains satisfying.

Along with that, Gunn shows Superman saving the lives of innocents, both human and animal alike, noticeably taking time to emphasize individual acts of heroism amid the urban destruction and “pocket dimension” nonsense.

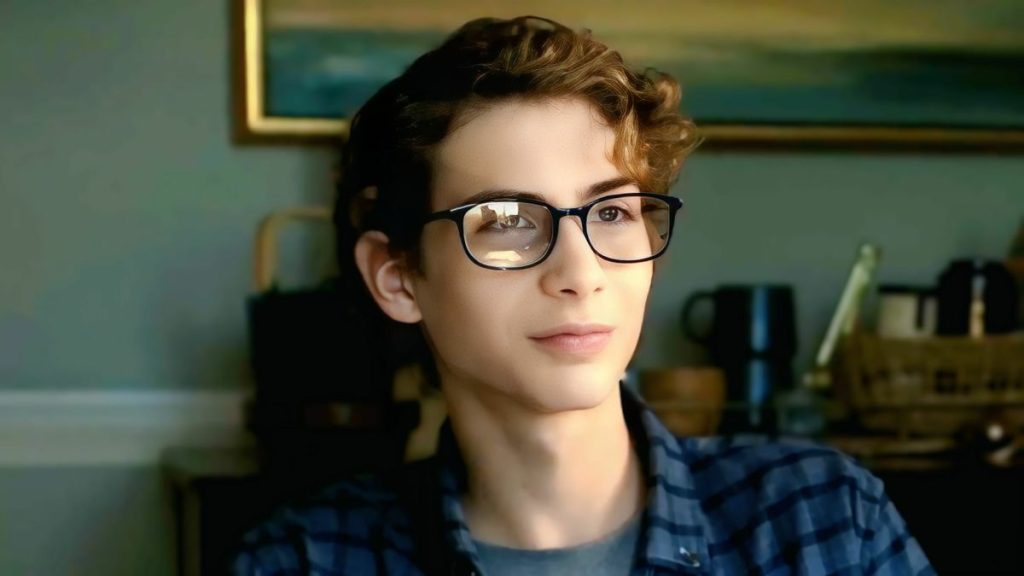

Hoult is equally threatening and pathetic, giving his Elon Musk-esque villain cartoonish mania and believable insecurity. Gathegi stands out among the rest of the ensemble with his droll comedic timing. The rest of the ensemble — including Skyler Gisondo as quick-witted Daily Planet reporter Jimmy Olsen and Sara Sampaio as Lex’s assistant, Eve Teschmacher — smoothly fit into Gunn’s “comic book come to life” philosophy without getting much opportunity to stand out amid the film’s scatterbrained subplots.

Indeed, “Superman” has several mini-stories going on at once that, while important to the overall plot, take time away from Superman’s arc, making clear that this film represents the start of a franchise, not just a standalone story.

It’s all quite visually striking — Henry Braham’s wide-lensed cinematography helps make the film’s more imaginatively bonkers and surprisingly weird sections easy to follow, if a tad bland in more “grounded” places— but “Superman” blends together in a jumble of noise and predictability (with some childish, distracting sexism thrown in for good measure) when the third act wraps up.

Gunn maintains his trademarks as a filmmaker, incorporating expected quip-filled humor, catchy needle drops (alongside a reverent score by John Murphy and David Fleming), and 360-degree shots of cartoonish violence when it strikes his fancy.

There’s merit to how unapologetic the film’s politics are. Gunn paints clear parallels from the Boravian conflict to current events and how those with vested interests at the highest levels of power continue cycles of evil. Gunn’s faithful rendition of Superman (essentially a refugee) honestly believes in “doing good,” no matter the consequences.

This choice is quietly radical, albeit hammered home with melodramatic force via the screenplay. Sure, “Superman” places these topics in a standard mold at the end of the day, but there’s still honor in spreading these messages in a summer blockbuster.

What “Superman” ends up being, then, is an above-average comic book film that subverts expectations in some ways while playing the same old tune in others. Nerds will be satiated, and bigots will be angered. A “super” film, however, this is not.

“Superman” is a 2025 fantasy-action-adventure-superhero film written and directed by James Gunn and starring David Corenswet, Rachel Brosnahan, Nicholas Hoult, Nathan Fillion, Isabel Merced, Wendell Pierce, Skyler Gisondo, Sara Sampaio, Anthony Carrigan, Edi Gathegi, Alan Tudyk, and Beck Bennett. Its run time is 2 hours, 9 minutes, and it’s rated PG-13 for violence, action and language. It opened in theatres July 11. Alex’s Grade: B

Alex McPherson is an unabashed pop culture nerd and a member of the St. Louis Film Critics Association.